Warsaw, Poland’s capital, is the largest city in the country, with about 1.8 million inhabitants.

Its historic old town is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The history of the city is tragic. It is a succession of invasions, wars, administrative restrictions. The most destructive episode took place during World War II with the creation of its ghetto, and we could not visit the city without learning more.

For this reason, we decided to register for 2 guided tours. The “free-walking-tours” you’re getting to know. The first was based on Warsaw’s Jewish community’s history, while the second led us to discover its old town.

For the first one, our meeting point is in front of All Saints Church, in the center of the Jewish community.

Warsaw’s Jewish community

Our guide began by telling us about Poland’s Jewish community and why it was the largest one in Europe before World War 2.

Three main reasons:

- The decision of King Kasimir the Great and his successors to offer refuge to persecuted Jews in other European countries.

- The creation by the Emperor of Russia Alexander III of the “Pale of Settlement,” an area that then included Poland and Belarus and where the Jews from Russia had an obligation to settle.

- A high birth rate in the Jewish community.

The city also experienced a large influx of Jews in the 19th and 20th Centuries. During the interwar period, Jewish Warsaw flourished. Hundreds of foreign artists, actors, writers, and journalists moved to Warsaw.

After this introduction, we headed to the Nożyk Synagogue, the only pre-war synagogue that has survived the war.

Built between 1898 and 1902, it was damaged by an air raid in 1939 and was restored after the war. It was then part of the small ghetto, and the Germans used it in 1941 as stables and warehouses.

Nowadays, it’s still active.

Towards the remains of Warsaw Ghetto

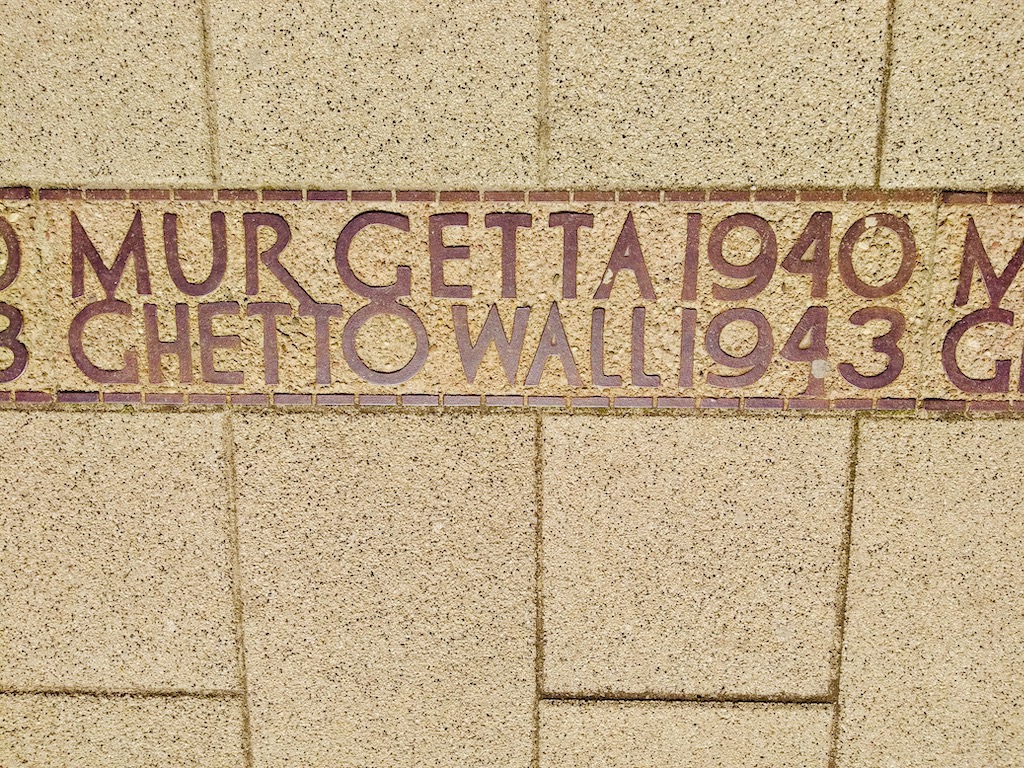

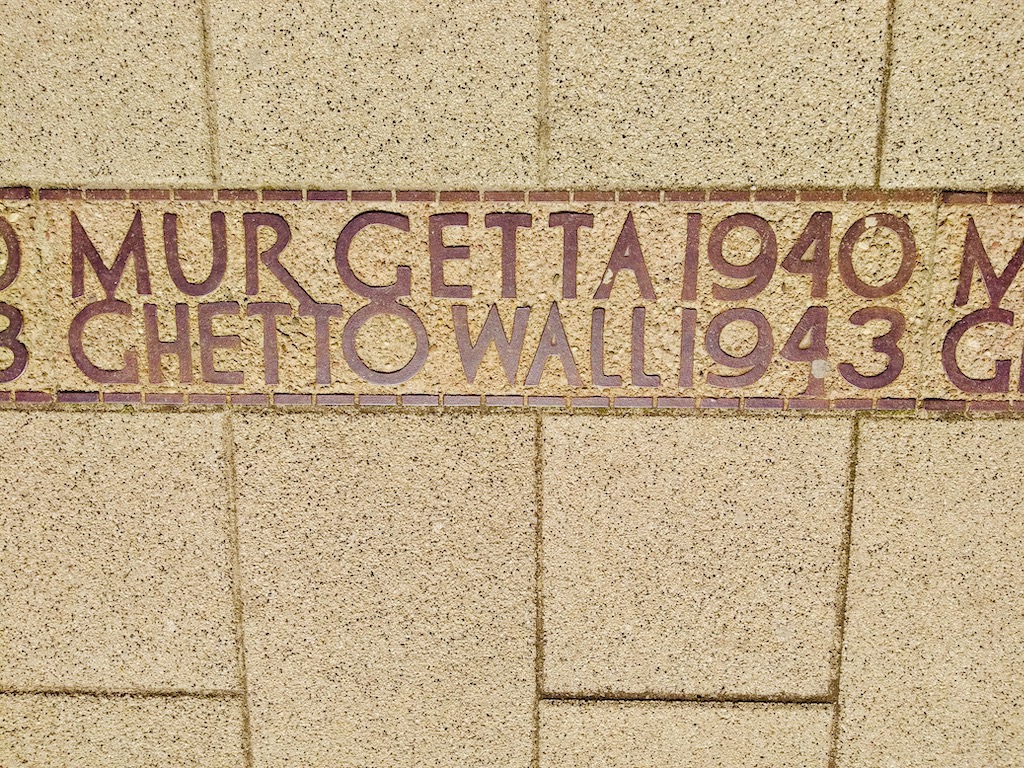

We headed to one of the original walls of the Jewish ghetto located at N˚ 11 Waliców Street, a ghetto’s boundaries. These walls can be found in different parts of the city and are the last vestiges of the ghetto left there in memory.

To get there, we took Grzybowska Avenue and crossed one of Warsaw’s new neighborhoods.

Waliców, old ghetto district.

Warsaw ghetto

In the winter of 1939-1940, the Nazis began persecuting the Jews, and the order to transplant Jews was given on October 2, 1940. They had 1 month to move to the Jewish quarter, which then officially became a “contagion zone,” forbidden to German soldiers.

Eighty thousand non-Jews left the area, and 138,000 Jews settled there. The ghetto was closed on November 16, 1940, and a perimeter wall was built.

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest Jewish ghetto in the Nazi-occupied territories in Europe.

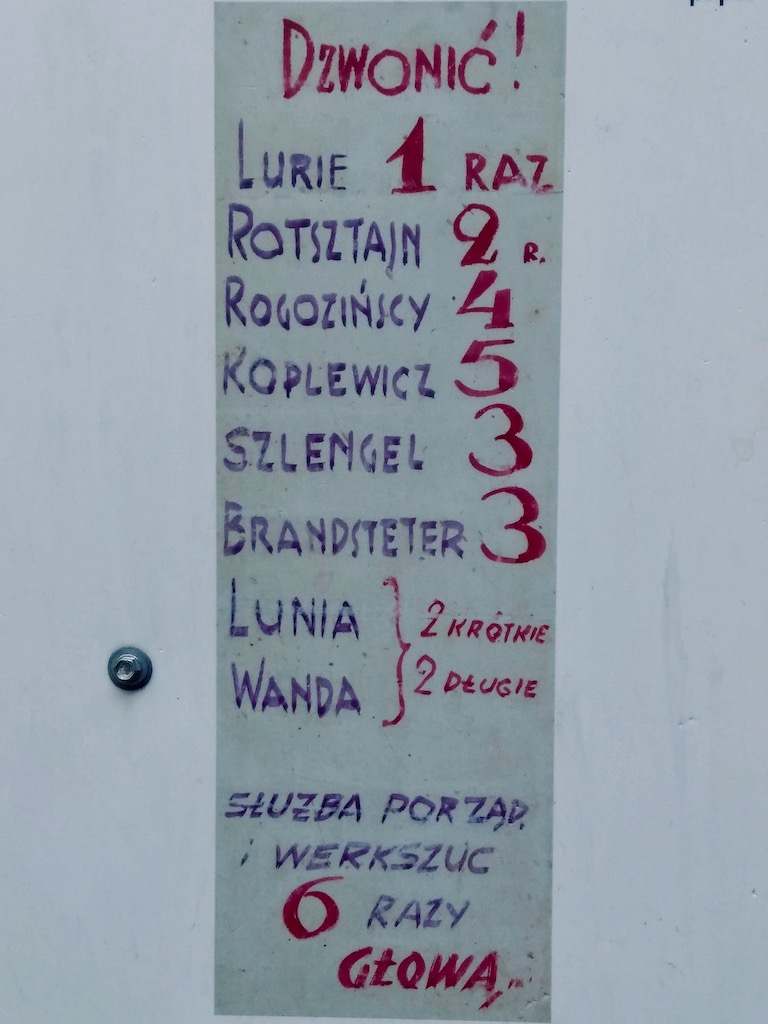

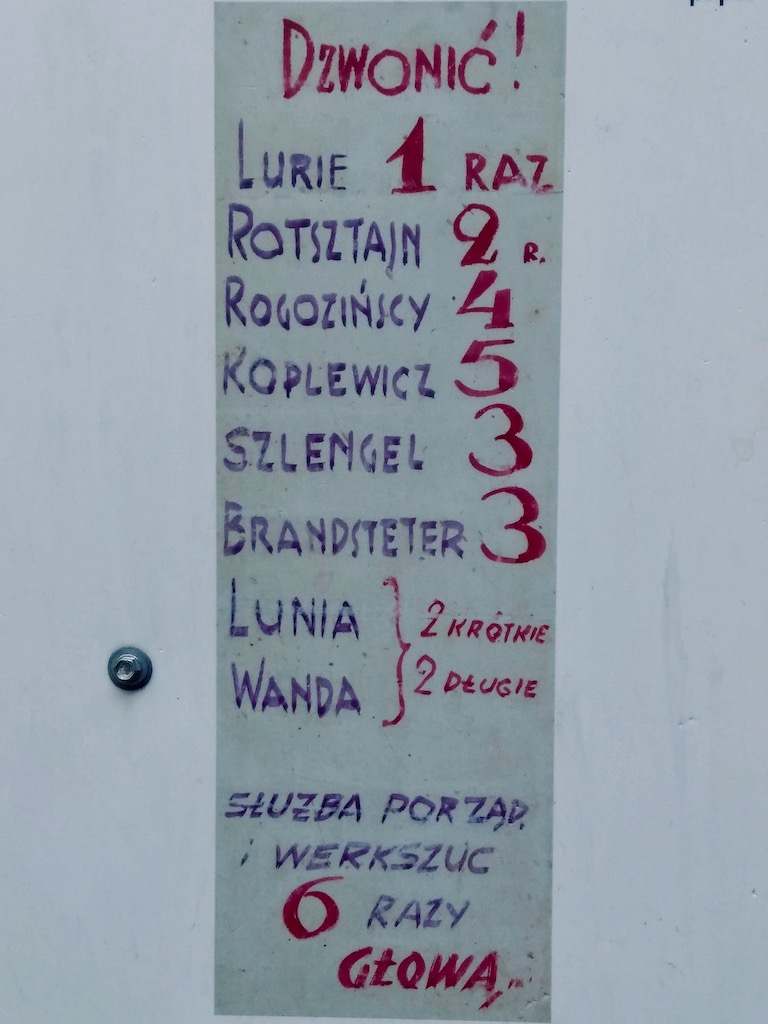

The ghetto was overcrowded. As many families lived together in the same apartment, a note on each front door specified how many times one needed to ring the bell to reach a specific family.

We continued our tour through the city to get to the old footbridge site that connected the small and the large ghetto. This footbridge was the only place from which the ghetto inhabitants could see the outside.

Janasz Palace

We passed Janasz Palace, a historical building dated from 1874. It was built for the financier Janasz, according to the French palaces’ characteristics, with a neo-baroque façade.

Today it is on the shortlist of buildings that suffered little during World War II. In 1970, the exterior and interior were restored to their original states.

We arrived at the feet of the columns that mark the location of the footbridge.

Our guide pointed us to a building a little further. It is the only one that survived the destruction of the ghetto. One can see it in a lot of archival photos.

He also explained to us that the tram line that still runs today on this street was, at the time, the only link between the ghetto and the outside world. It crossed the ghetto by passing under the footbridge to allow non-Jewish Poles to travel the neighborhood.

It is hard to imagine today, the neighborhood as it was. Our guide brought some archival images to help us picture it.

To finish our visit, we went to the Monument of the Heroes of the Ghetto square. Along the way, our guide told us about the insurrection of the summer of 1942.

The insurection of Warsaw Ghetto

In the summer of 1942, deportation began to the concentration camps. Following this great deportation wave, the Jewish resistance was organized against the German occupying forces between 19 April and 16 May 1943.

It is the best known and most commemorated act of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust. The resistance was stronger than expected by the Nazis, even if the outcome was certain given the forces’ imbalance.

The end of the ghetto

The final act was the destruction of the great synagogue in Warsaw, and the burning of the ghetto ordered by Hitler, by ideology but above all, to mark the spirits.

Those who returned in 1944-45 could no longer find a trace of the neighborhood where they lived. This “sea of ruin” covers 300 hectares, the equivalent of 420 football fields.

We arrived at the Monument of the Heroes of the Ghetto. The monument was inaugurated in 1948, five years after the beginning of the uprising. It is located close to where the clashes began.

It represents a group of Jewish fighters armed with Molotov cocktails, pistols, and grenades. A young woman holds a child in her arms. The flames behind them represent the ghetto burned by the Nazis.

Opposite the monument is the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

It was built on the symbolic Warsaw Ghetto site and was inaugurated on April 19, 2013, for the 70th anniversary of its insurrection. It is about Jewish tradition and culture during the thousand years of their history in Poland.

Our visit ended, and we thanked our guide for telling us about this episode in his country’s history with such passion.

Conclusion

Do this visit without hesitation. It is a beautiful moment of sharing and emotions, and our guide knew how to set the right tone in his speech.

We could not visit the Polin Museum due to lack of time, but I think it would have added a great plus to this visit.

Wow what an amazing post. I only spent a weekend in Warsaw a few years ago and didn’t dig deep into its Jewish history. I did visit the polish uprising museum, which is one of the best museums I’ve ever visited.

Thank you for sharing this post!

Thanks. I didn’t have time to go to museums during my stay in Warsaw. So the Warsaw Uprising Museum will be another museum I will have to add to my list of museums I must visit when I’ll go back to Warsaw.